Disruption by Design: Entrepreneurs pave a new road to space

The silence was deafening. Almon Strowger’s telephone hadn’t rung in days, but he knew people were still dying. One of only two undertakers in Kansas City during the late 1800s, Strowger had a problem. The wife of his primary competitor served as the telephone operator and worked the switchboard at the local telephone exchange. When callers requested an undertaker or even Strowger by name, she deliberately directed the calls to her husband instead.

Strowger spent years complaining to the telephone company, but this failed to solve the problem. Undeterred and knowing little about the technology behind the telephone system and infrastructure, he was nonetheless inspired to solve the problem himself. The result was the invention of the first automated telephone switch, which allowed callers to direct-dial without having to go through a local operator. His inspiration led to a creative solution and resulted in the redesign of the entire telephone industry.

Countless examples illustrate how people outside a particular establishment can become inspired to solve a problem, often with little to no expertise or background in the field itself. John Dunlop, a veterinarian, invented the first pneumatic tire in 1887 to provide a softer ride for his son’s tricycle. Leopold Godowsky, Jr. and Leopold Mannes, both musicians, invented Kodachrome film in 1916 because they felt cheated after seeing the film Our Navy, which was advertised as a color film but had extremely poor color quality. Hedy Lamarr, a popular actress during the 1940s, and George Anthiel, a composer, developed a secret communication system known as “spread spectrum” technology to help combat the Nazis during World War II. Spread spectrum technology went on to provide the foundation for today’s cellular phone technology and other wireless communications.

In 1985, psychologist Robert Sternberg and his colleagues at Yale conducted a study in which they asked people about the characteristics of highly creative individuals. A common thread ran through most of the answers—the idea that creative people tend to reject accepted, conventional ways of thinking and instead support ideas perceived as fresh and new. By choosing to think differently, these creative people also understand and accept the risks of failing in order to ultimately succeed.

Thinking differently combined with the willingness to take risks often results in a change or disruption of the status quo. In the early 1990s, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen coined the term “disruptive innovation” as an innovation that creates new markets and value networks which displace established market leaders and existing alliances. Compared to established companies and organizations, which tend to drive what’s called “sustaining innovations” that try to stay relevant and meet market needs through proven, incremental modifications and improvements, disruptors are often underrated, and their ideas are viewed as low-market solutions—until they’re not. By taking root in the bottom of the market and building on lower costs, higher accessibility, or other real or perceived advantages, the company or product becomes more appealing than the competition.

For example, video streaming completely caught the entertainment industry off guard. While video stores and cable and satellite providers were continuously improving their products in predictable, incremental ways, Netflix, viewed as a low-cost, low-market video rental house, became the largest subscription provider in the U.S. and completely disrupted the Hollywood ecosystem. Video stores have all but vanished and cable and satellite providers are trying to hang on to an ever-shrinking slice of a pie that’s quickly being consumed by the likes of Disney, Apple, Amazon, Sling, YouTube, and other streaming services.

In a 1959 essay, author Isaac Asimov wrote, “A person willing to fly in the face of reason, authority, and common sense must be a person of considerable self-assurance. Since he occurs only rarely, he must seem eccentric (in at least that respect) to the rest of us.”

Enter the space billionaires.

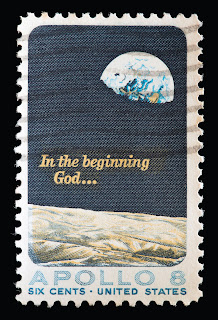

By joining the rapidly developing commercial space race, billionaire-backed companies such as Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin, Elon Musk’s SpaceX, and Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic have flown in the face of reason and common sense. NASA’s Apollo and shuttle programs showed just how complicated, expensive, and risky spaceflight can be, and when Blue Origin, SpaceX, and Virgin Galactic were all founded within a few years of each other, many thought they all shared the same collective pipe dream. However, since their respective beginnings 20 years ago, SpaceX has had multiple successes while lowering costs across the board, and Blue Origin and Virgin may follow suit. SpaceX in particular has managed to free up more of NASA’s budget for other areas of space exploration and research.

NASA now has contracts with more than 300 publicly traded companies and the global space industry could produce revenues of more than one trillion dollars by 2040. With companies like Relativity Space, currently at work 3D printing entire rockets; Rocket Lab, whose Electron rocket uses unique engines powered by battery-charged electric motors; or Axiom Space, which is building the first private space station; opportunities for disruption in the NewSpace business continue to grow.

The most creative, innovative people are also the most successful in propelling ideas forward. Google is one of the largest technology companies in the world not because it created a new, disruptive technology, but because its founders thought they could offer something that was a little better than what was already on the market. In that same vein, just as people watched Star Trek and went on to actually design and innovate many of the ideas the show presented (such as cellular flip phones, video communication, and talking computers), today’s commercial space visionaries and leaders watched both the Apollo and shuttle programs identifying concepts ripe for improvement.

During the Apollo years, NASA knew it was unsustainable to continue using expendable rockets to achieve its goals, which was one motivation for the space shuttle. However, it was the outsiders who seized on the financial necessity of reusable spacecraft and embraced the creation of designs that were both cost-effective and safe. Meanwhile, NASA’s SLS rocket, designed for the Artemis lunar landing program, is still a single-use booster and could easily be viewed as simply a “sustaining innovation.” While improving on old ideas and building on new ones, the commercial space sector is now changing the way people think about spaceflight and continues to disrupt what was once the sole domain of governments and nations.

Disruption takes time, however, and doesn’t usually change markets quickly. It can take years, and sometimes decades, for new ideas and approaches to take hold. While NewSpace companies appear to many to have achieved quick success, these successes were built on almost two decades of setbacks and failures. Rockets exploded, software failed, and components malfunctioned. So when one sees SpaceX launch a bunch of private citizens with no real experience into space (funded by yet another billionaire), remember that this journey comes on the shoulders of people who have taken risks, overcome setbacks, and weathered ridicule to achieve disruptions in a business that is only about 60 years old.

As more visionaries and companies enter the NewSpace industry and build bigger and more efficient spacecraft and support systems, they will change the traditional look and feel of spaceflight as we know it today. Government-sponsored monopolistic contracts will continue to erode, launch prices will continue to plunge, and the future of space travel and settlement––most certainly shaped and designed by disruptors––will look very different in the years to come.

Comments

Post a Comment