100 Years...If Ever (A perspective on reaching Mars)

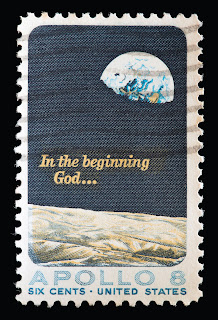

Bill Anders, the Apollo 8 astronaut who took the legendary Earthrise photo while orbiting the Moon on Christmas Eve in 1968, was recently interviewed about his thoughts on getting people to Mars. As a member of the National Academy of Engineering for his contributions and research to nuclear engineering, including the study of space radiation, Anders understands the challenges and doesn’t believe we will be able to overcome the hardships of extended periods of time in zero-G or exposure to radiation in space on the human body. The part of the interview that really strikes a chord, however, isn’t about the rigors of travel to Mars, but his statement, “I’m not sure we will ever get humans to Mars. Maybe a hundred years from now.”

A hundred years from now, if ever?

What does a hundred years of innovation look like? Newspapers in the 1920s are full of articles predicting how things might have changed by the 2020s. While some of the predictions were way off, many have come true. Jason Feifer, editor-in-chief for Entrepreneur magazine, wrote about an article by W. L. George in 1922, which offered an important truth about how the world works. George begins with the claim that though “the advancement of science will be amazing” by 2022, he didn’t think it would be mind-blowing. In other words, based on the technological leaps that occurred in the prior century, what’s so special about traveling to Mars when the world has already made the leap from the horse-and-buggy to the railroad?

Feifer goes on to say that while people think of the current digital era as unprecedented, a century ago, people had already witnessed transformations deemed to be impossible––such as information traveling faster than physical objects using the telegraph or light magically appearing in homes through the use of electricity. While traveling to Mars would be amazing, it might not be the most incredible feat ever achieved.

Change is more often than not the result of people embracing opportunities and solving the litany of problems that come with them. While some changes may seem like monumental, overnight advances, they’re almost always the result of a significant number of incremental steps.

In last century, people have witnessed a staggering amount of innovation. Some of the major advances include the development of the television, the jet engine, liquid and solid fuel rockets, the electron microscope, the photocopier and laser printer, nuclear energy, microwave ovens, fiber optics, biometrics, genetic engineering, transistors and later microchips, personal computing and the internet, satellites and GPS, autonomous driving vehicles, and solar cells—the list goes on and on.

If someone were plucked from 1922 and magically transported to 2022, they would be mystified by today’s world. But since we don’t have the luxury to observe the world that way, people must adapt and display their resilience again and again when it comes to change. Many innovations are simply improvements to prior ideas, and people are able to adapt by incorporating the new while still using the old. My great-grandmother was born in 1895 and during her 95-year lifetime, she saw a world that relied on the horse-and-buggy for transportation and effectively adapted to the automobile before accepting the development of spacecraft capable of sending people to other worlds (not to mention living through two world wars and the Great Depression). She never really seemed amazed by these innovations, but took them in stride, just as everyone else does.

Change can be difficult to see, but its effects have a profound impact. The ability to imagine something that doesn’t yet exist requires the ability to visualize abstract ideas and elaborate upon them. The people who possess this ability are those most often able to identify new opportunities. Imagination is the seed for new ideas that help cultivate the emerging technologies and changes that inspire more imagination, more ideas, and so on.

For others, however, predictions of future possibilities can be frightening, especially if those ideas are viewed as threatening irreparable harm or changing their culture in unacceptable ways. The thought of change often ignites a range of emotions in people, not the least of which is fear and the negative possibilities that come with it. Fear is typically a function of the unknown, and our inability to let go of the emotion keeps us from taking proactive steps toward change or taking advantage of new opportunities. Luckily, most people don’t seem to give the changes occurring around them that much thought, especially as they focus on solving their own problems in daily life. They tend to change as the world around them changes, just as my great-grandmother did.

It’s impossible to predict the future, but sometimes we can get glimpses of it. Whether it’s product announcements in the media or live demonstrations at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, new ideas are regularly on display, such as robotic workers to help with worker shortages across the country, development of the metaverse—a virtual reality world where users can interact and have experiences similar to the real world—or the latest technological unveilings by companies like Apple, Samsung, Tesla, SpaceX, and Sierra Space.

Sierra Space was on full display at this year’s CES and featured their partnership with Blue Origin on the Orbital Reef space station initiative. The most interesting aspect of Sierra Space’s involvement was how space settlement and tourism are now part of the mainstream in technology and private investment, something unheard of not so long ago when space was the exclusive playground of large governments. According to John Roth, Vice President of Business Development for Sierra Space, their plans for long-term success are to continue to establish many business and non-space partnerships and raise $1.4 billion in private capital––the largest amount yet for the commercial space sector.

There’s no doubt that venturing to Mars poses many challenges. According to Dr. Pascal Lee, planetary scientist and chairman of the Mars Institute, there are five major obstacles to human health and wellbeing on the Red Planet (survival time related to those risks is listed in parentheses):

• Low atmospheric pressure (seconds)

• No oxygen (O2), and toxic levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) (minutes)

• Very low surface temperatures (hours)

• Martian soil and dust, which is extremely fine, abrasive, and toxic (days to weeks)

• Ionizing radiation (months to years)

However, while traveling to the Moon also poses many of these problems––albeit not to the same degree––it’s only a three-day journey home if something goes wrong. Still, we were able to solve these and many other problems—50 years ago—because that’s what people do.

Perhaps Anders is correct, and it will take at least a hundred years to get to Mars. If it does, human inability will not be to blame. With the incredible amount of technology being developed at exponential rates, traveling to and settling Mars is less a technical problem than one of will.

Just as the Space Race with the Soviet Union drove America to the Moon in the 1960s, there should be a reason or legitimate need to go to Mars. Perhaps another superpower with conflicting values will ignite another space race. Perhaps the egos and competitive drives of the growing number of space billionaires will get us there. Perhaps a planet-killing asteroid heading towards Earth will light the fire. Or maybe it will be something completely unknown. What if prospectors on the Martian surface discovered large pockets of solid rhodium, which currently trades at about $14,000 an ounce (as compared to gold at $1,800 an ounce)?

Comments

Post a Comment