Thinking Inside the Box: How Nuts, Bolts, and a Bigger Box are what made NASA Successful during the Space Age

|

| Bolts from the original Launch Umbilical Tower (LUT). |

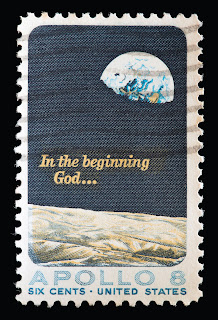

I’m a collector of sorts, especially when it comes to Apollo memorabilia. There’s something about being surrounded by these artifacts that ignites and inspires my creativity. While window shopping an online space auction recently, something grabbed my attention––two large bolts including washers and nuts. Though most people probably wouldn’t get too excited about a couple of bolts, these were special, as they were part of the original Launch Umbilical Tower used to launch the Saturn V rockets to the Moon. The bolts were huge, about eight inches in length, weighed about five pounds each, and still had portions covered in the original orange-red paint.

Seeing these bolts got me thinking about everything that went into putting a man on the Moon. While we celebrate the 50th anniversary of those missions, the focus tends to be on the astronauts as heroes in the same way they’re portrayed in films like First Man, Apollo 13, and The Right Stuff. Yet these bolts represent something much greater: the more than 400,000 scientists, engineers, administrators, managers, programmers, construction workers, mathematicians, secretaries, drivers, factory workers, food service personnel, seamstresses, custodians, and everyone else that made getting to the Moon possible in the first place. These people represent the foundation on which the Apollo Program was built, a massive infrastructure of people and resources that had to be effectively managed in a short period of time to accomplish Kennedy’s goal.

So why was NASA successfulwith Apollo? When Kennedy set the goal of landing a man on the Moon within a few short years, he committed the country to do something it had never done, that no one had any idea how to accomplish. We didn’t have the tools and equipment, the spacesuits, the micro-computer technology, the rockets, or even facilities such as the Launch Umbilical Tower. It wasn’t just about what we knew we didn’t have, it was also about not understanding what we would need to be successful, like trying to solve a puzzle without knowing the final image.

“Thinking outside of the box” is a phrase commonly used to encourage creativity by thinking in different or unconventional ways. The phrase is popular because it espouses an important idea, one that is catchy, memorable, and easy to visualize. Thus, to solve this big, unknown puzzle, it may have been tempting for NASA to take a giant leap out of the box, but they would have done so at their own peril.

Often, during the quest to think outside of the box, some basic in-the-box principles tend to fall by the wayside. But when these principles are retained, they provide a deeply-rooted foundation, one that allows us to venture beyond the box and look at things differently, yet return when necessary. Unfortunately, these time-honored values can get lost during the pursuit of what’s outside. The box itself is the key to success, not by leaving it, but by expanding it through increased learning, creativity, and innovation all while holding true to your basic foundation.

When NASA began this process, they started by building on what was already in the box. Following World War II, the United States had built a tremendous aviation industry. The military and its contractors, the same contractors who would ultimately build the Saturn V, knew how to design and build state-of-the-art aircraft—complex machines manufactured and assembled with parts and subsystems built by other contractors. Through the testing and monitoring of the systems of high-altitude, high-speed aircraft, Chris Kraft was able to build on that knowledge to create Mission Control. NASA relied on this experience to move from aircraft development to complex spacecraft and support systems. Through this process and based on what they had previously learned, they built the Apollo Program on the following principles:

Positive is Innovative:

Attitude is a game changer. It reflects the tone of leadership and dictates the response to failure. If you want others to be successful, maintaining a consistent, positive attitude is paramount, as people can easily become discouraged. A positive attitude by those in charge, as well as a positive environment built on trust, can help them overcome these feelings and develop a renewed sense of energy. The leadership at NASA during the development of Apollo had this very attitude, which was emphasized during a recent interview with Apollo Flight Director Gerry Griffin:

[NASA] leadership trusted us to do our jobs and focus on the things we knew had a good chance of working. We didn’t try to do anything wild or approach it willy-nilly. We knew that to launch someone in a rocket with about six-and-a-half million pounds of explosive propellant was really risky. NASA leadership always approached what we did with a positive attitude and with the mindset we would do this as simply and quickly as possible without taking any unnecessary risks.

This style of leadership has been proven throughout history and never requires one to leave the box. The people that led NASA during the 1960s assembled strong teams of doers, many who were only in their twenties. They found and nurtured those who could work both individually and collaboratively. Knowing that individual effort impacts the outcome of the entire group, they were willing to work to improve individual performance and build trust between team members.

Built-In Resilience:

Simplicity and redundancy was built into all of the Apollo spacecraft. According to George Low, the manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office and later the deputy director of NASA, “Build it simple and then double up on as many components or systems as possible so that if one fails the other will take over.” This design philosophy minimized functional interfaces between pieces of hardware, which allowed contractors to work on their own projects independently. Hardware underwent extensive testing to ensure reliability, and thousands of tests were conducted day after day for the duration of the program.

Through extremely detailed, realistic, and repetitive simulations, teams of mission controllers, flight crews, and contractors were able to practice and hone their skills. Mission rules and flight procedures were created allowing everyone to develop the resilience necessary to effectively react to issues as they occurred. Challenges are rarely solved by creating more detailed calculations, but rather by a teams’ ability to think differently beforethings go wrong and develop detailed strategies should that occur. A fear of failure often keeps people from reaching their full potential, impeding their growth. Through the use of regular and repeated simulations, leadership was able to remove the negative connotation of failure. “What if” became a driving force within Apollo’s development, designed to “expand the box” so that thinking outside of it wouldn’t be necessary during split-second decisions when lives were at stake. Contrary to the high level of emotion displayed in Mission Control during the movie Apollo 13, the team was very calm, and intently focused on their respective tasks, because of the repetitive nature of their training.

Think Big, Execute Small:

Effective leaders are able to “see” a big leap, a possible positive outcome or challenging opportunity, and then visualize and implement each small step necessary to achieve it. NASA leadership ensured that their missions were extremely well planned and executed down to the minute. Making correct decisions was paramount to success and crew safety, but leaders actually listened to their teams despite the time constraints they were under. If their feedback and concerns weren’t valued by leadership, those people were unlikely to fully support decisions, even if they were the correct ones. Gerry Griffin discussed this leadership approach:

We had the perfect arrangement in the early 1960s. NASA leadership would put decisions at the right level. We had a very large group of young people with little experience, but [with] fresh ideas. We had great leadership that understood we hadn’t ever done this before, so they decided to tap into their ideas and actually listen. Good communication was critical. It didn’t matter at what level you were within NASA at that time—if you had something to say, you were encouraged to speak up. I’d see some young man who couldn’t have been more than 25 years old wearing old horned-rimmed glasses stand up and start speaking while everyonelistened. Sometimes their ideas would be rejected, sometimes not, but listening carefully encouraged everyone to actively participate in the process. This kept people motivated and excited despite the pressure and stress.

Planning for each mission included all phases of operation and execution with the intent to gain the maximum experience possible on each successive flight, and learn without stretching the equipment or the people beyond their ability. Despite the short deadline, NASA administration followed the time-tested lesson of the tortoise and the hare; they began by taking the time to plan correctly from the beginning and use what they already knew. This approach ultimately sped up their implementation towards the climax of the program—the lunar landings.

At the end of my interview with Griffin, he said, “I knew we were doing something that was really important, and I would frequently think, ‘Hey, this isn’t easy. Let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves and make sure that at the end of the day, it’s a nuts and bolts business where everything has to come together, get bolted together, and work together, without flaw.’”

As I look at the bolts from the Saturn V Launch Umbilical Tower now sitting on my desk, I will forever be reminded how “expanding my box” is a better strategy than thinking outside of it.

© 2019 Anthony D. Paustian. Dr. Anthony Paustian is the author of A Quarter Million Steps, the Vice President of Marketing for the National Space Society, and a success coach for Bookpress Publishing. He can be reached at tonyp@BookpressPublishing.com.

Comments

Post a Comment